A sectoral analysis of the UK economy provides more granular evidence that Ben Broadbent’s assumption of labour hoarding and lower productivity growth currently impacting the UK economy is the most plausible explanation of the breakdown between rising employment and output. Research highlights that it is the financial services sector driving the anomaly with the on-going restructuring of the sector accounting for labour hoarding. Subdued productivity at the macro level is being impacted by declining productivity in the financial services sector due to a swathe of onerous regulations on top of substantially higher capital requirements. In order for productivity growth to get back on an upward trajectory, it will require both a slowdown in regulation in conjunction with a new generation of managers who are able to raise productivity with lower levels of demand, rather than depending on unsustainable rising demand which drove profits throughout the Great Moderation.

Introduction

In recent months a debate has opened up in the UK with regards to the breakdown of the relationship between rising employment and output. One of the best summaries of this debate is a speech by Ben Broadbent of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC). The speech commented on why rising employment in the UK economy had not filtered through to rising output. Broadbent postulated two potential reasons for this unusual situation. Firstly he suggested that labour was being hoarded, although given rising employment this is clearly a very unusual situation. The second is a slow-down in the underlying productivity growth of the economy. Broadbent suggested that it was most likely a bit of both. Although Broadbent’s argument is well made, one of the challenges with macroeconomic-based analysis is that it does not reveal what is happening at the micro level which would provide more detailed information as to what might be causing the economy to behave in such a way. This point was made by Hayek in his seminal paper The Use of Knowledge in Society in 1945, where the information of time and place that makes up the market is extremely valuable in understanding the changing dynamic of the system. In the spirit of Hayek, Credit Capital Advisory has undertaken a sector-based analysis of the UK economy based on 500 listed firms. Assuming that what is taking place in listed firms is reasonably representative of what is happening in the broader economy (although this is always open to question), the analysis provides further evidence supporting Broadbent’s assumption that labour hoarding and falling productivity is the cause of the anomaly, driven mainly by the performance of the financial services sector.

Labour hoarding in financial services

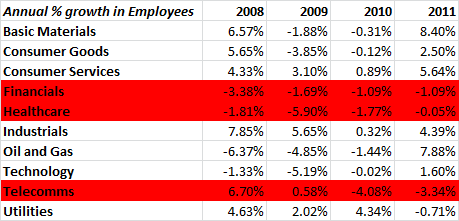

Table 1 provides a summary of the annualised percentage growth in employees across the main sectors of the UK economy. In 2011 most sectors saw a robust growth in employment. Such a growth is clearly contrary to the idea of labour hoarding as that would mean firms would be hiring people they didn’t actually need. However, the analysis highlights three sectors that have seen two consecutive years of falling labour. One of the most common causes of labour hoarding is when industries are restructuring due to shifts in aggregate demand which is generally characterised by falling employment. Managers at the firm level are reducing headcount to take cost out of the business, but not at a fast enough rate as they are concerned that when demand picks up again they are not sufficiently staffed to meet that demand. The challenge for the manager is that it is very difficult to predict the bottom of the cycle, hence labour hoarding becomes a way of trying to mitigate the problem of not being caught out when the cycle does turn.

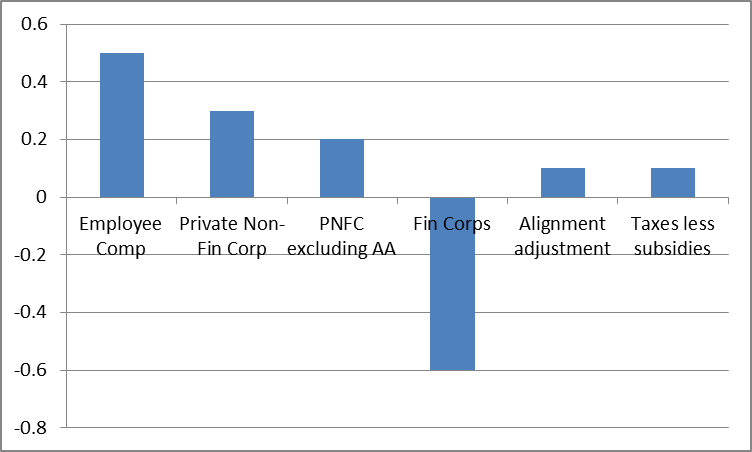

Of the three sectors with falling employee participation rates the healthcare and telecoms sectors can largely be discounted as explaining the anomaly seen at the macroeconomic level as their impact on the wider economy is limited given their relatively small footprint. The data for financial services however provides compelling evidence as why labour hoarding is showing up in macroeconomic analyses as the financial services sector contributes roughly a third in gross value added to the UK economy. The existence of labour hoarding implies that the financial services sector has not come out of its downturn that started with the onset of the financial crisis. Further evidence of the financial services still being in negative territory is shown in chart 1 below using contributions to GDP growth from income measures. This data clearly shows why output growth has remained so sluggish.

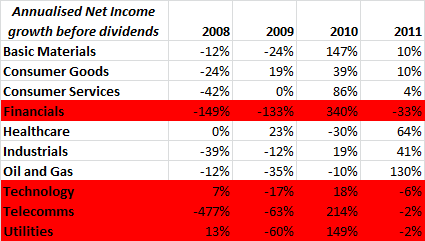

Another way of benchmarking the employment data is to try and understand what these sectors think about future profit growth. Clearly rising employment in a sector suggests that the outlook for profit expectations is improving hence the demand for labour. An analysis of the trend in net income growth before dividends in table 2 provides further evidence that financial services is weighing down the economy. Although technology, telecoms and utilities also showed a fall in the rate of net income growth, the levels are small which can partially be explained away by the confidence levels of the results. Despite the fact that the financial services sector had a bumper year in 2010, this appears to have been an anomaly and the latest data suggests that the sector has not yet reached the bottom of its cycle.

Table 1: Growth in employees by sector

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, Credit Capital Advisory

Note on data: The data doesn’t stipulate where companies are hiring, so it will only provide an indication of future earnings growth overall, with the implicit assumption that some of the hires are being made in the UK.

Table 2: Growth in net income before dividends by sector

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, Credit Capital Advisory

Chart 1: 2011 Contributions to GDP growth under the income measure

Source: ONS

Productivity decline in financial services

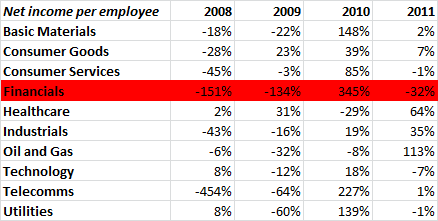

If we now run an analysis of productivity growth by sector using a simple net income per employee measure, we get a similar picture with productivity growing in most sectors of the economy. Clearly this measure is not a true productivity figure given exogenous factors (changing levels of demand) impact the net income figure. What matters in the medium term is of course how managers react to changes in exogenous factors to ensure that productivity growth can be maintained when demand stops rising. This relationship does seem to be somewhat asymmetric as when exogenous factors increase demand, managers do not tend to respond in kind to improve efficiency but rather ride the wave of rising demand. This is why many macroeconomic studies find that productivity growth tends to rise faster as the economy is coming out of a recession when managers are forced to think about how to get more output from the same input or the same level of output with lower inputs.

In terms of the data indicating rising productivity, one would expect to see fewer large swings between positive and negative values with steadily increasing values. Table 3 shows that the financial services sector stands out from all other sectors since the onset of the financial crisis with its negative productivity growth punctuated by an anomaly in 2010.

Table 3: Productivity Measures

Source: Thomson Reuters Datastream, Credit Capital Advisory

Implications for the UK economy

Given the importance of the financial services sector to the UK economy in terms of its contribution to output and employment as well as its role in providing credit to the economy at large, until the sector is back on its feet it will continue to act as a brake on the UK economy’s future rate of growth. Hence, it is worth attempting to understand what factors have prevented the sector from turning itself around. Without doubt one of the major reasons why the sector has been hit is due to the new swathe of regulations. The cost of regulation has negatively impacted the productivity of the sector. Moreover, the required increase in capital has also impacted productivity growth with banks having to work much harder to increase profits. One lesson that politicians and regulators might want to take from the crisis is that it would have been prudent to have waited until the economy had recovered from its predicament before forcing such dramatic changes on the banking sector. This very point was made over a decade ago by the Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz who argued that ordering banks to recapitalise in the depths of a recession is exactly the wrong thing to do if your objective is to increase employment and growth.

Another reason behind lower productivity growth is that true productivity growth in the sector has remained weak for many years including during the Great Moderation. This is less about economics and more about management theory. The challenges faced by managers in a boom are very different to those in a bust. In boom times, the main focus by management teams is how to recruit people fast enough and increase capacity to meet the rising level of demand. Thus to maintain rising profit growth the main challenges is to ensure that costs grow at a marginally slower rate than revenue. When the boom falters, companies find themselves with too much headcount and the restructuring begins. However, in a paradigm where demand is not expected to rise substantially, the approach managers will need to take will be very different. Indeed, the financial services sector, particularly banks, may have to fundamentally rethink what their core business is in order to generate the kind of productivity growth that will be required to drive profits. A report by McKinsey in 2010 highlighted how banks may respond to the new paradigm with changes to their business models.

Conclusion

Broadbent’s conclusion that the breakdown of the relationship between employment and output is because of labour hoarding and falling productivity growth is backed up by data showing that the main driver of this anomaly is the financial services sector. Until the sector has completed its restructuring and the raft of onerous regulations slows in conjunction with a new generation of managers in place to drive productivity, it is likely that the sector will continue to constrain GDP growth. The financial services sector remains critical to the future of the UK economy in terms of accelerated output and employment growth. This is a fact that policy makers ought to recognise if they want to see significant falls in unemployment and rising levels of output.

Further Reading

Bai, Rios-Rull & Storesletten, Demand Shocks as Productivity Shocks

A Field, US Economic Growth in the Gilded Age

B. Broadbent, Productivity and the Allocation of Resources

F. Hayek, The Use of Knowledge in Society

McKinsey & Company – Basel III and European Banking

J. Stiglitz & B. Greenwald – Towards a New Paradigm in Monetary Economics