The last 6 months have been a boon for credit cycle investors who avoided significant losses arising from the fall in bond prices. The data has been clear for some time, however, that the market was mispricing bonds. See here and here. The market has now realised its error with bond yields rising to more appropriate levels as argued here.

Many market commentators continue to be taken in by the naïve “inverted yield curve” indicator that a recession has been pending for many, many months and appear to be somewhat surprised by the resilience of the US economy. This assumption is flawed because it assumes that economic growth prior to the pandemic was reliant on low interest rates and therefore it would be unable to deal with a significant increase in the cost of borrowing.

This assumption is grounded in the monetary theory a la Fisher and Keynes which assumes that economic agents will continue to borrow until returns fall towards the cost of capital. However, this theory has little bearing on reality as argued here. During the period 2018-2019 the return on capital was 11.6% compared to the BBB 5 year funding rate of 3.6%. Hence, only the most profitable projects were undertaken rather than at the margin, which is why firms’ investment plans are less sensitive to interest rate rises. This is though very different to the what is happening in the eurozone.

Furthermore, the central bank by keeping interest rates low was signaling to economic agents that everything was not great with the economy, which in turn impacted future expectations and decision making; a point Keynes made in the General Theory (that I also referenced in my 2012 book Profiting from Monetary Policy). In essence, had central banks started increasing interest rates in 2016, then it is highly likely that growth would have been higher. Moreover the data is clear that firm’s investment decisions are made during a RISING interest rate environment which generally signals an improvement in the economic outlook.

This is not to argue that there are no risks on the horizon. The non-bank financial sector looks increasingly risky as noted here. However, future risks are also partly contingent on where interest rates end up.

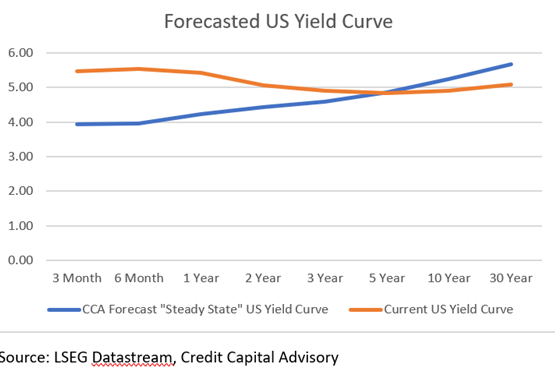

Over the last few months, Credit Capital Advisory has modelled the future path of interest rates across the yield curve based on inflation oscillating in a 2.5% to 3% window. Our conclusion generates a yield curve that is likely to fall at the short end but increase further at the long end.

Chart 1: Forecasted vs Current US Yield Curve

Our forecasted yield curve indicates that the Federal Reserve has now stopped increasing rates – which I would say is broadly in line with consensus. However, we think these rates will fall only gently over time to maintain growth in the economy. Our view is that five year rates are probably about where they need to be. However 10 and 30 year yields still have some way to go on the upside.

An upward sloping yield curve is how a bond market should be operating under “normal conditions”. The reality is that since 2008, it has been anything but normal: a point that has often been ignored by market commentators.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks