A recent Odd Lots discussion with Austan Goolsbee, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, raised an important philosophical question about the nature and level of interest rates. As Joe put it, why do we have to put up with mortgage rates at 8% if inflation returns back towards target when prior to the pandemic interest rates were about half that level?

While consumers of course want access to cheap credit, most central banks worry about cheap credit in case it raises the rate of inflation persistently above a 2% target. The question for central bankers is to what extent continued cheap credit might impact the future rate of inflation. In addition, it is critical to question central bankers’ assumptions that excess credit creation is absolutely fine as long as it doesn’t impact inflation.

In this blog I want to address two specific points. The first is that while interest rates were much lower before the pandemic, they were in fact driving excess credit creation and hence were not sustainable. The second is that interest rates are not returning to pre-pandemic levels because we are now in a new economic regime – one which is inherently more inflationary.

Cheap credit is not the right solution

The fact that interest rates were lower before the pandemic without causing inflation is similar to the situation we were in prior to the global financial crisis when monetary policy created an explosion of cheap credit that wasn’t impacting inflation.

For credit analysts like myself who had long been sceptical of contemporary monetary theory which assumes the economy is grounded in general equilibrium, the financial crisis offered a chance to try and change the debate. My 2012 book Profiting from Monetary Policy published by Palgrave and favourably reviewed by Bill White – former chief economist at the BIS – and The Economist was my attempt to provide a credit framework to think about the economy, rather than a monetary one.

The Swedish economist, Knut Wicksell, lies at the heart of both approaches. He argued that although excessive credit accumulation would negatively impact an economy, as long as the money rate of interest rate equaled the natural rate of interest (read marginal return on capital) – which he assumed would also stabilise prices – the economy could be maintained at an equilibrium level. The natural rate therefore was ALSO defined as the equilibrium real interest rate consistent with price stability.

Wicksell’s approach has been hugely influential with regards to contemporary monetary theory including the work of the New Keynesians Michael Woodford and John Taylor. Up until the global financial crisis central banks thought that they were in control of inflation via interest rate policy. This is why academic economists struggled to explain the crisis in 2008. As Willem Buiter remarked in 2009 the last 30 years of research in monetary economics have been a waste of time focused on abstract and unrealistic models. In essence, the model used by central banks to maintain economic stability had instead resulted in economic instability.

This was because at the heart of Wicksell’s assumptions there was a fundamental flaw that his fellow Swedes (who became known as the Stockholm School) highlighted – but were largely ignored by the Anglo-Saxon dominated profession. When productivity increases it raises the marginal product of capital (natural rate of interest) and reduces prices. This fall in prices was problematic for Wicksell who wanted price stability, hence Wicksell’s approach would have been to reduce the money rate of interest in order to maintain price stability. But this would push the two rates further apart resulting in a monetary disequilibrium.

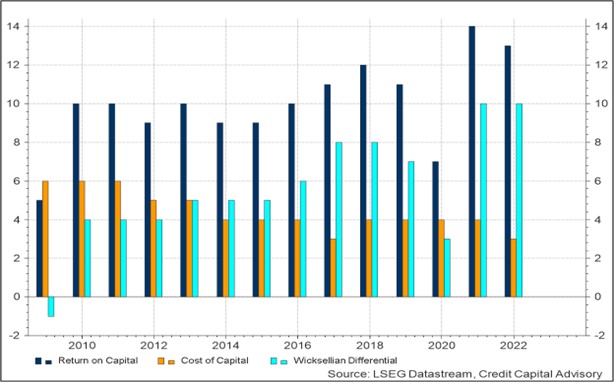

In essence, where there is a sustained difference between the marginal product of capital and the money rate of interest, it results in excess credit creation – which in turn causes a monetary disequilibrium. This was also the case in 2019 where the return on capital was 11.2% and the cost of capital was just 3.7%. This wasn’t inflationary given that the excess credit creation was inflating asset prices – a point noted by the Stockholm School economist Bertie Ohlin in the 1930s (which was also the case in the runup to the GFC). In essence, the level of interest rates in 2019 were not sustainable as chart 1 indicates.

Chart 1: US Wicksellian Differential 2009-2022

The implications of the chart are that the economy would have been fine with slightly higher interest rates in 2019 given that the return on capital was so much higher and firms DO NOT invest at the margin – a point I have explained here. Indeed, one of the flaws in the theoretical literature on interest rates is the idea that investors will keep supporting projects as long there is a positive return. But this is not how the real world works and why the return on capital is often significantly higher than the money rate, hence investment is far less sensitive to interest rate rises.

Had interest rates started to rise from 2016, the major difference would have been a lower rate of increase in asset prices which would surely have been a good thing. Furthermore, there is a strong argument that after the initial decrease in interest rates in 2008 due to the fall in the marginal product of capital, by 2013 there was limited value in maintaining interest rates at the zero lower bound. Indeed, if lower interest rates are signaling to consumers and firms that things are not great – it may act as a deterrent for them to increase their level of consumption or investment – a pointed noted by Keynes in the General Theory. Hence had central banks started to raise rates then, this would have indicated to agents that the outlook was improving which in turn may have resulted in increased output.

The new inflationary regime

The second point is that even if you are wedded to the New Keynesian approach and do not care about the destabilizing effects of excess credit creation – the future path of inflation is not going to be the same as the 2019 period. One crucial aspect of this argument is that inflation is not purely an endogenous concept. Indeed, there is an increasing body of literature that inflation is partly a global phenomena which is why inflation remained subdued during the pre-GFC phase given the positive labour supply shock of China and India entering into global supply chains. This is why inflation fell in countries where central banks targeted inflation BUT ALSO where they didn’t target it. Many central bankers were aware of this prior to the GFC, but most did not openly accept that their job had largely been outsourced.

From Profiting from Monetary Policy

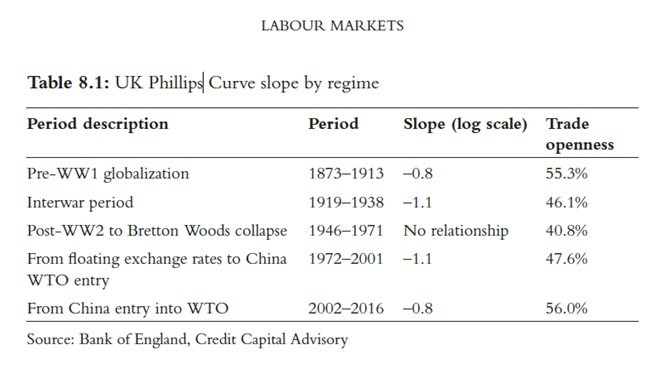

The future path of open trade and a growing labour supply is now in reverse with a shift towards protectionism and a fall in labour supply. This is why Charles Goodhart noted in his last book that we are entering into an inflationary period. In addition, my own research on the nature of the Phillips Curve indicates that more open economies are less likely to be impacted by inflation.

From All Roads Lead to Serfdom 2022

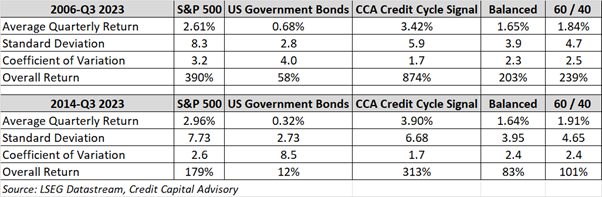

The bond market has struggled to fully appreciate this shift until very recently. Although I had no ambition when writing my 2012 book to influence the way central banks operated, the focus of the book was to highlight to investors that they could profit from this fundamentally flawed approach to monetary policy. This is why credit cycle investors were not long – long maturity bonds over the last 6 months and still aren’t. Since 2006 this approach to asset allocation has resulted in significant excess returns to a buy and hold strategy with lower volatility. And since I started publishing notes in 2014, the excess returns have continued.

One reason credit cycle investing is not particularly widespread is that the signals are quarterly – and many fund managers want to be able to understand what is happening either daily or at least weekly. The problem for financial market practitioners is that it’s hard for investors to disentangle useful information from noise – which the credit cycle does a much better job at doing. As one family office portfolio manager said to me many years ago, “credit cycle investing is a bit like the Slow Food revolution. Most people don’t have the patience for it despite that the fact that it turns out to be better for you”.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks