The Chancellor of the Exchequer’s big new idea is to more than double the amount of subprime loans in order to expand home ownership. This will of course lead to a housing boom, fuelled by falling credit standards, and then a spectacular bust costing the UK tax payer potentially as much as half of the £135 billion of loans he expects to be issued as part of the policy. Lending to high risk borrowers between 2004 and 2007 wasnt a very good idea. It still isn’t a very good idea.

Overview

The Chancellor of the Exchequer in his budget speech today announced a new scheme called Help to Buy. The explicit aim of the policy is twofold:

1. Increase the number of subprime borrowers through a government backed equity loan of 20% of the value of a property based on a 95% loan to value ratio for any new build.

2. Provide a government guarantee of £30,000 for any re-mortgaged loan for both new and existing homes with the aim of incentivising mortgage providers to provide loans to subprime borrowers. The chancellor has estimated that this guarantee may end up supporting up to £130 billion of loans that wouldn’t have otherwise have been made due to the low credit worthiness of the borrower.

The FT headline was “Property moves seen as game changer”. This is quite clearly the case, only the title of the game being played is “Welcome to the next crisis” The trigger for the recent financial crisis was of course caused by a fall in house prices that led to subprime borrowers defaulting on their loans and the financial institutions that made the loans having insufficient capital to absorb those losses due to excessive leverage. So what impact might this policy have on the UK economy given the stream of data we have been able to collect from the recent financial crisis?

Subprime Mania

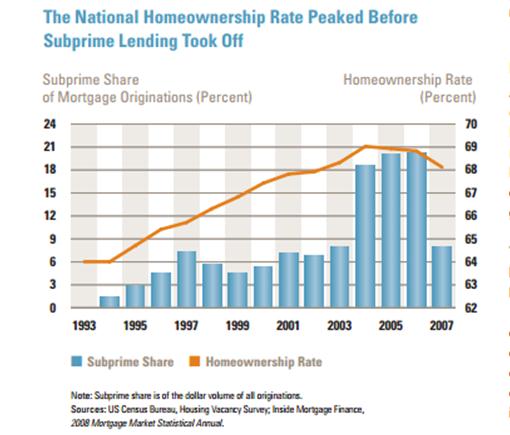

By the summer of 2007, the share of subprime issuance had risen from lows of around 7% in 2001 to 20% in 2006 as shown in chart 1 courtesy of the Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University’s publication ‘The state of the nation’s housing 2008’

Chart 1

Subprime or non-conforming issuance in the UK is roughly 8% of the £1.25 trillion outstanding mortgage debt or around £100 billion. So George Osborne’s big idea is to basically increase subprime issuance from around 8% of total lending to around 17%. That figure is pretty close to where the US market got to in 2006. Clearly this release of credit into the economy is likely to have some short term positive effect on the economy. The problem of course is that the success of the policy depends on house prices continuing to rise in order to maintain the credit boom. Up until now, the British financial sector has been able to manage reasonably well the risk of lending to subprime borrowers. However any such increase in support for subprime lending is likely to boost house prices, which in turn will increase the value of the underlying collateral giving the impression that these loans are less risky than they actually are. This is the process of reflexivity that George Soros has been describing for most of his career which is how credit markets function. Unfortunately this process of reflexivity at some stage will come to an end when suddenly there are no more subprime borrowers to maintain what is in effect a Ponzi scheme. This leads to falling house prices and an acceleration of defaults, which in turn sends asset prices down further. Reflexivity of course works both ways generating nonlinear trajectories of asset values.

What happens when house prices fall?

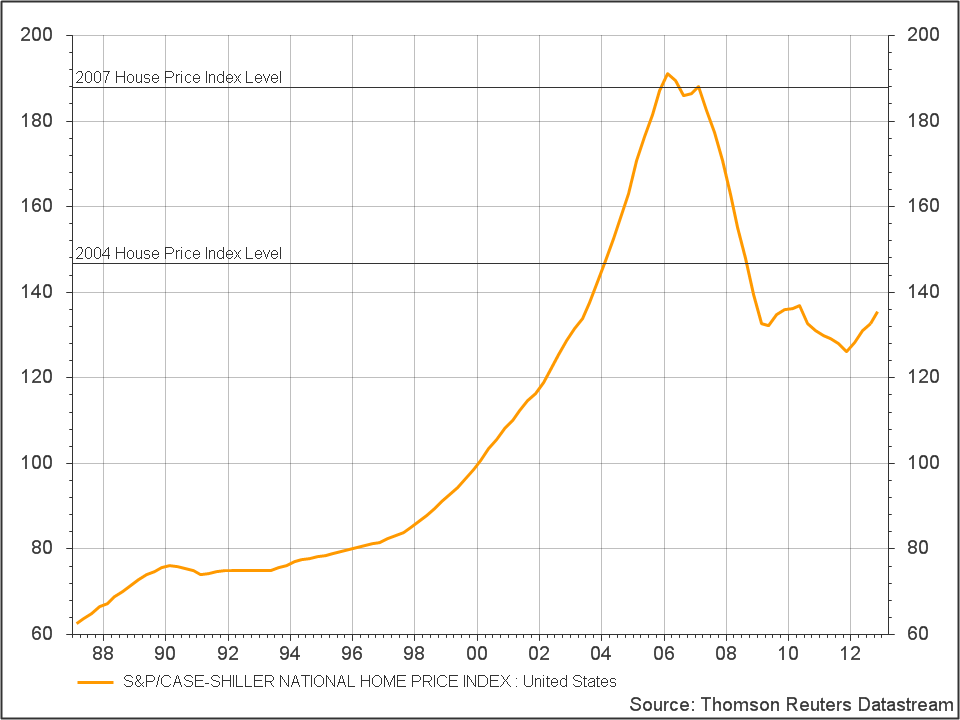

One important lesson from the US subprime crisis was that when negative equity began to rise due to falling house prices, many home owners realised they would never be able to recoup any of the equity in their house and foreclosed on the property. Crucially, the extent of the foreclosure depended on the vintage of the subprime issuance. Chart 2 below shows the S&P Case-Shiller US house price index highlighting the difference in value between 2004 and 2007. In essence subprime issuance not only drove house prices up to significantly higher levels, but the vintages issued at higher levels were plagued with much higher levels of default due to higher levels of negative equity.

Chart 2

Unfortunately for the global economy, between 2004 and 2012, the house price index fell from 147.39 to 135.41 equating to an 8% fall. However, from 2007 to 2012 the index fell from 187.97 to 135.41 equating to a 28% drop. So what might such a drop in house prices have on the loans which in turn will lead to rising losses within the mortgage providers, and of course the government having to step in and bail out the mortgage lenders?

Data from the credit default swap market during the crisis period highlights what happened to the value of the loans and the impact it might have on the financial system. By 2007, the 2004 vintage (subordinated tranches) were already trading at a discount at around 70 cents to the dollar. The value of these bonds represented by the credit default swaps on these bonds fell around 75% to just under 20 cents in the dollar. The 2007 vintage which was already pricing at a significant discount by the fall of 2007 trading at 25 cents in the dollar fell almost 90% in value to around 3 cents in the dollar. The market was indicating that these loans were mostly going to default and therefore had little value. This is where the unexpected losses hit the financial institutions that had loaned out the money in the first place. Moreover, falling house prices obviously puts prime borrowers under pressure too, which in turn can exacerbate the situation.

The secondary market data however does overstate the case somewhat because the good quality borrowers in these pools of mortgages were able to refinance leaving the worst loans behind. However, it was these bad loans that led to the catastrophic events we have seen. Clearly if the UK has only an 8% fall in house prices once the boom ends, all these new subprime borrowers amounting to £130 billion would have fallen into negative equity. As we saw in the United States, house prices might fall by as much as 30% based on loans issued later in the boom due to rising prices during the boom. This would mean that not only a large chunk of the £130 billion of loans would mostly likely default, but that it would have a massive knock on effect on the rest of the economy. As such it is highly unlikely that the new capital regimes in place would be able to absorb such large losses requiring the tax payer to pay another large bill.

The real reason of course for the housing crisis in the United Kingdom is that the price of land is sticky due to favourable fiscal treatment. This means that the profits from productive enterprises are constantly eroded by the extraction of economic rent by the landowners. This is one of the reasons why productivity in the British economy is lower than its international counterparts. A more sensible approach to boosting the economy would be to tax land values. This would have reduced the returns to economic rent, increased profits for productive enterprises leading to higher investment and jobs. But that is not going to happen. The only thing that tax payers can do is learn how to profit from boom and bust. The history of asset bubbles suggests that failure to recognise this will only end in tears for tax payers.