Passive investing in market index funds has been labelled a “parasitic” business. However, re-designing index rules to account for corporate moves such as mergers and acquisitions could make passive the new active.

This year’s Nobel Prize in Economics was a good one for the passive investment model. One of the winners, Eugene Fama, was rewarded for his work on the efficient market hypothesis (EMH), the idea that share prices reflect all available information. His work has been supported by the fact that active funds that attempt to pick winning stocks have demonstrated that they are mostly unable to beat the market.

Investors are taking note, putting an increased amount of money into index trackers at the expense of active funds. But there’s a catch — passive funds ignore market signals resulting from corporate activity, particularly M&A, which are central to EMH. This has resulted in lower profits for passive managers and lower returns for investors as acquisitions have destroyed shareholder value. This lack of engagement with corporate management has also generated criticism, with active managers labelling passive management as a parasitic industry.

By redesigning index rules to take account of market signals on M&A and potentially other areas of corporate activity such as executive remuneration, passive funds will be able to generate improved profits and better returns for their clients. These new index rules can generate automatic voting triggers based on each corporate action without having to build expensive teams to engage with every company. Such a revolution in index design would thus permit passive funds to play an active role in improving corporate governance.

Shareholders get what they deserve?

Fund managers play a crucial role in ensuring that management teams deploy capital effectively, which is particularly important when it comes to mergers and acquisitions. However passive and many active managers have traditionally not played a significant role in holding management teams to account. This has often been a source of frustration to policy makers given fund managers’ pivotal role in corporate governance. This point was emphasised in a recent debate hosted by Board Intelligence on how to improve corporate governance. The view that “shareholders need to take their governance duties more seriously” was a resounding one. As assets in passive funds grow, this may become more of a problem given the high costs of engaging with management teams contradicts their low cost business model. There are, however, ways of redesigning passive funds that can take account of corporate governance issues without the high cost of engagement. This can be done by using the ideas of Fama himself – that the market is the best aggregator of available information at the company level.

Corporate finance theory postulates that when a public company decides to deploy capital for an acquisition, the information released about the project is absorbed by the market which then provides a signal as to whether the proposed deployment will create or destroy value. If share prices fall, executive teams ought to shelve the project. If they continue with the project, shareholders should act to protect their investments and vote against the management team.

The problem is that these signals are ignored by passive and many active funds. As a result, value destroying deals have proceeded with the support of institutional shareholders generating lower returns to savers. Fund managers’ profits are also negatively impacted given that assets under management are lower than they would have been.

It is important to note though that not all mergers and acquisition require shareholder approval. For example, in the U.K., any acquisition that meets any of the “class 1” tests which includes acquiring a firm that exceeds 25% of the bidder’s market capitalisation must be approved by shareholders. This differs from the United States where shareholder approval is often not required for even large transactions.

Credit Capital Advisory has analysed a number of deals since 2007 where the market signalled that the deal was expected to destroy value. They include the RBS acquisition of ABN Amro, Hewlett Packard’s acquisition of Autonomy and the Softbank acquisition of Sprint.

Who says turkeys don’t vote for Christmas?

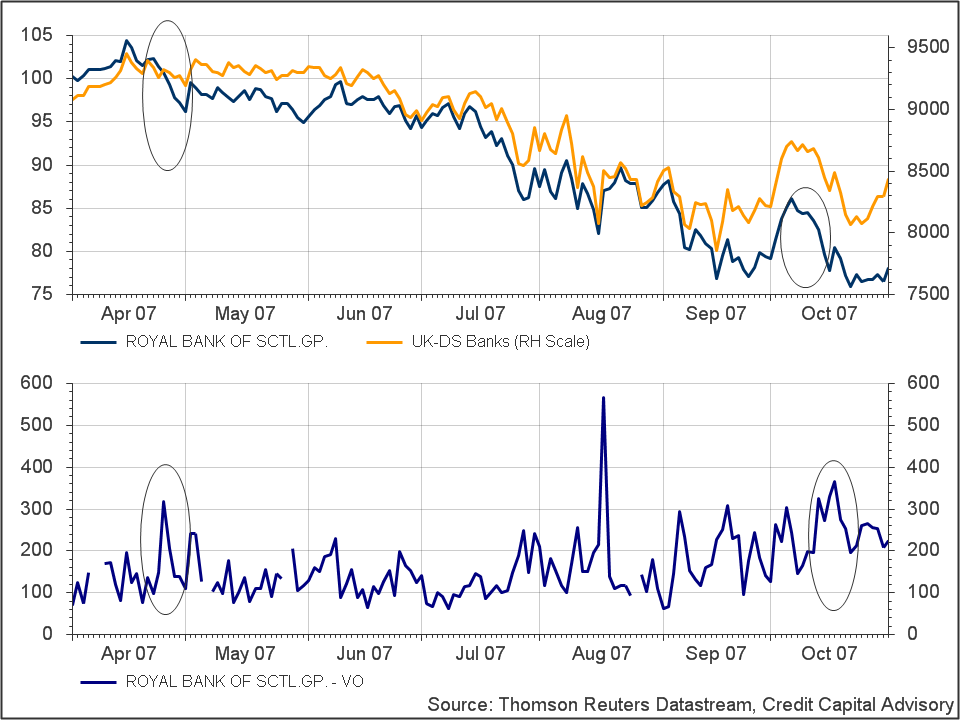

On April 24, 2007 the RBS share price fell relative to the U.K. banks index following its initial bid of €72 billion for ABN Amro. RBS sold off again on Oct. 5 when Barclays withdrew from the deal. The five-day market signal revealed a fall of over 4% in the share price. On Aug. 10, 94.5% of RBS shareholders who voted were in favor of the value-destroying merger.

Chart 1: RBS acquisition of ABN Amro

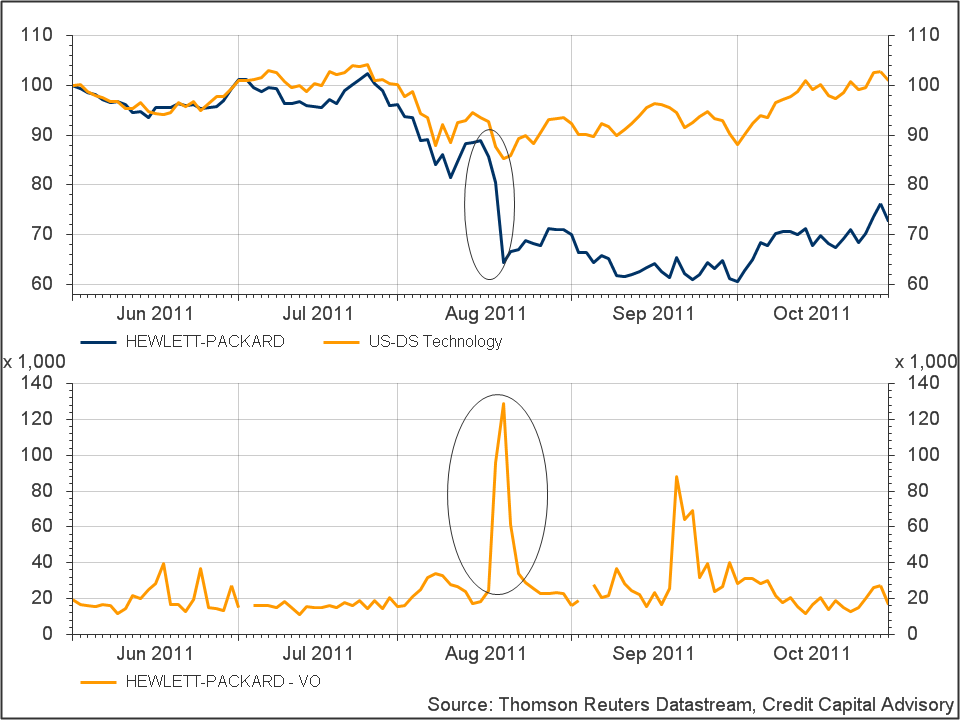

On August 18, 2011, Hewlett Packard announced a $10.3 billion acquisition for Autonomy. The market was distinctly unimpressed, with a spike in volume and a 22% sell-off over five days. HP still managed to secure 87.34% of shareholders’ votes.

Chart 2: Hewlett Packard acquisition of Autonomy

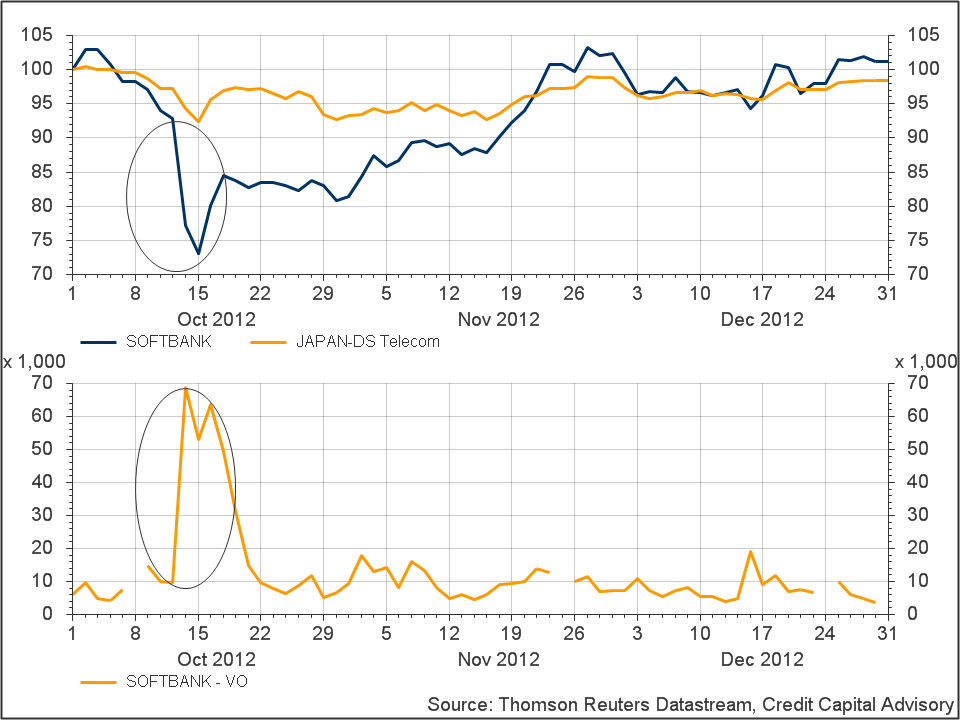

On Oct. 11, 2012, rumours of a bid for Sprint by Softbank percolated through the market. The bid which was confirmed on Oct. 15 at $20.1 billion led to a sell-off of Softbank stock resulting in a 9% fall over the trailing five-day period. The deal was subsequently raised to $21.6 billion on June 10, 2013. The Softbank deal acts as a useful test case to ascertain to what extent the market generates false signals. By the end of 2012, Softbank’s share price had recovered and since March 2013 Softbank has outperformed the Japan Telecom index by nearly 35%. The reasons for this outperformance, however, have been mostly driven by Softbank’s investments in GungHo Online Entertainment and the continuous stream of stellar earnings from Alibaba. Softbank is the largest shareholder in Alibaba and is also benefitting from the interest surrounding Alibaba’s expected IPO. Furthermore the Sprint stock price has fallen over 10% against the U.S. telecoms index since mid-August. Hence from a corporate governance perspective the Sprint deal should have been noted by shareholders if their goal was to maximize shareholder value.

Chart 3: Softbank acquisition of Sprint

Is passive the new active?

Since the inception of passive funds in the 1970s, there has been little change to their basic stucture, with the main focus being on driving down costs. However the failure of passive funds to take account of market signals surrounding corporate actions highlights how their profits, and the returns to investors, have been negatively impacted. This is because engaging with individual companies on corporate governance issues is a time consuming and expensive business. If passive indices could be redesigned to take account of market signals indicating destruction of shareholder value without significantly raising costs, then this would result in higher returns for investors and higher profits for fund management companies. Moreover, any increase in the level of engagement between shareholders and management teams would also have a positive impact on the way that companies are run. So how might such index rules be created within a passive framework?

The generation and implementation of rules to ensure that all M&A activity is value creating has a number of challenges. Firstly a decision needs to be made at what point the movement of the share price ought to be measured. Is it from an initial rumor of the deal or from the official announcement? The release of information to the market needs to abide by strict stock market rules, so although rumours do find their way out to the market, the announcement itself has to take precedent.

The second issue is to decide how long the market takes to digest the information and provide its aggregated view. An analysis of multiple deals suggests that between three to five business days is appropriate.

The third issue is related to the level at which the triggers would be set given the existence of statistical error. Such a rule might state that if the share price fell by more than 1% relative to its sector index then it would trigger an automatic “no” vote. Finally the issue as to whether shareholders have the right to vote on the acquisition needs to be factored in, which depends on the jurisdiction of the buyer and sometimes on the size of the acquisition. In certain jurisdictions shareholders may only have the option of selling the stock which would need to be taken into account. All of these stages can be automated, tested and implemented using basic quantitative finance techniques.

Such approaches to index redesign could also be extended to executive remuneration. In this instance if a company has underperformed within its sector, it could trigger a vote to prevent pay rising over a certain percentage. That way share price performance as part of general market growth but which is not related to the skill of the management team does not get rewarded.

Clearly once such rules are published and functioning, they can have unintended consequences as executive teams try and game the system. Although this is a distinct probability, such rules can be changed as fund management companies learn about the consequences. Of crucial importance is that passive funds, who are nearly always the largest shareholders, will be able to take their governance role seriously without having to increase their cost base to engage with firms.

Parasitic no longer

The passive management sector has a huge opportunity to change the way it interacts with the companies it “owns,” leading to increased profits and better returns. Utilising the ideas of Eugene Fama, that the market is the most efficient mechanism at synthesising all available company information, new index rules can be designed to prevent exposure to corporate actions that destroy shareholder value. The implementation of rules that would generate automatic voting triggers, would not only lead to better profits and higher returns, but also to improved corporate governance without the high costs of more traditional active engagement. This long overdue revolution in index design would go along way to countering the criticisms that the passive industry is a parasitic one. The result of this increase in activity around corporate governance implies that the distinction between passive and active funds may start to blur. Passive may well indeed become the new active.