A neo-Wicksellian analysis of the Chinese economy highlights that China is not experiencing a classic Wicksellian cumulative process as Japan did in the 1980s. A more pressing concern for investors ought to be the falling rate of profit. It is however plausible that the massive infrastructure investment being undertaken by highly leveraged local authorities could help drive the rate of profit back up at some point in the future.

Overview

Over the last few years, concerns have been consistently raised by analysts that the Chinese economy has been going through a substantial Wicksellian cumulative process, similar to the one that Japan went through from the late 1970s until its bubble burst in 1989. A Wicksellian cumulative process is where rising profits encourage an expansion of debt which at some point in the future becomes too large to be paid back leading to rising defaults and a crash in asset values and economic output. Analysts often cite the vast shadow banking sector which is largely financing the dramatic rise in regional and local government debt as evidence to substantiate this argument. However, an analysis of the time series available does not show that China is in the throes of a Wicksellian cumulative process. Crucially, China’s natural rate of interest has for the last three years been falling not rising, with the large rise in demand for credit being a function of local authorities embarking on massive infrastructure projects which have mainly been financed through the shadow banking sector from savings.

Without doubt the recent report from the National Audit Office highlighting that the level of local government borrowing was much higher than expected is a cause for concern. However the lack of a Wicksellian cumulative process suggests that the extent of credit growth into financial assets per se has not reached levels seen in Japan in the 1980s nor the US in the run up to the financial crisis. Furthermore, the strong fiscal position of the Chinese government suggests that defaults on local government borrowing are likely to be contained. Investor concern about China’s rate of GDP growth plummeting is not only therefore overblown but it also misunderstands what drives asset prices. Too many investors continue to make the error that a sustained rate of GDP growth filters through to higher corporate earnings and hence rising asset prices. Econometric evidence has consistently demonstrated that there is little correlation between these two measures. The performance of Chinese equities has been poor over the last three years because China’s natural rate of interest – or rate of profit has been falling since 2010. For equity prices to start rising again, there needs to be a jump in productivity growth and it is perfectly plausible that some of the massive infrastructure investment being undertaking by regional governments may provide just that. Alex Field’s research shows that during the Great Depression private and public investment in transport & telecommunication networks as well as in utilities led to the largest ever rise in productivity growth in the history of the United States. Investors should therefore be more concerned about whether this infrastructure investment could potentially boost productivity for Chinese companies rather than obsessing about the 7.5% GDP growth target.

Data issues and methodology challenges

The quality of credit disequilibrium analyses – which are based on micro foundations as set out in Profiting from Monetary Policy – are dependent on the availability and integrity of data. My reluctance to undertake this analysis for so long has been due to concerns surrounding the quality of Chinese company accounts data on top of my own experience back in the 1990s as a guest writer on economics and finance for the China Post. However, on analysing a much larger set of Chinese companies within the Worldscope Datastream database of over 2,500 companies, the data was a great deal more consistent than expected. Hence the quality of the natural rate of interest signal is reasonably robust. The more problematic data on China is in fact around the cost of funding. Data for the government bond market begins around 2006 which makes the calculation of the Wicksellian Differential impossible. In this instance to calculate the Wicksellian Differential the five year spot rates are used as opposed to the five year moving average. This proxy implies that direct international comparisons will be misleading to some extent.

China natural rate of interest and Wicksellian Differential in decline

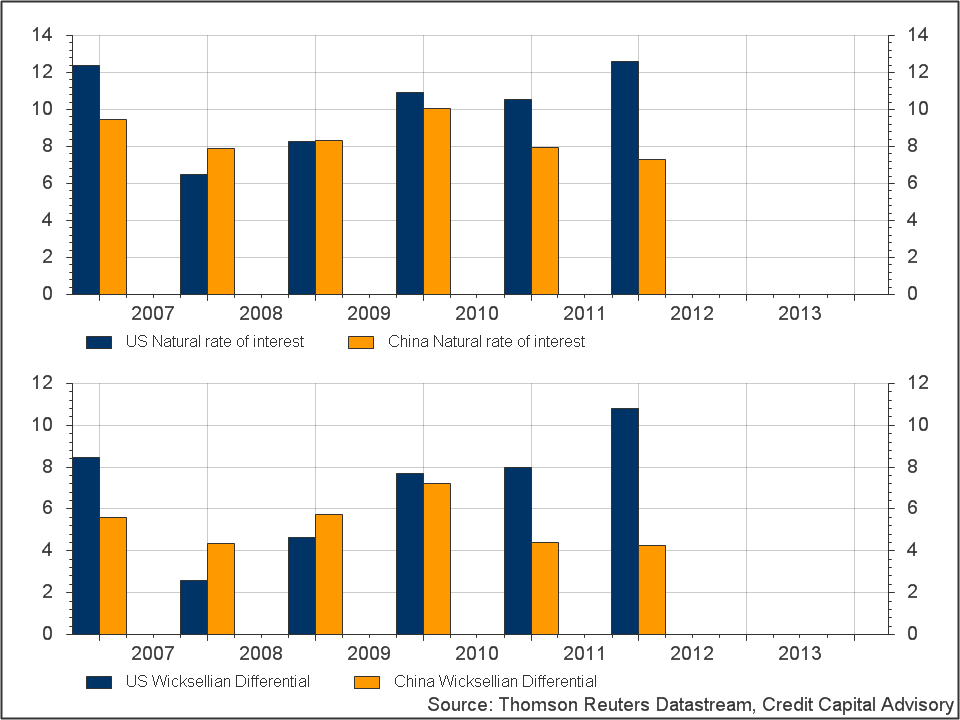

As shown in the top pane of chart 1.0, between 2007 and 2010 the natural rates of interest of both China and the US pursued similar paths declining in 2008 before rising again. However since 2010 the two countries have diverged considerably with the natural rate of interest rising in the US but declining in China. The data for 2013 once available is expected to have maintained this divergent trajectory.

Chart 1.0 China vs US natural rate of interest and Wicksellian Differentials

The bottom pane showing the Wicksellian Differential – which takes the cost of funding away from the natural rate of interest – shows a similar trajectory. As stated above these two rates are not directly comparable due to the limited government bond data series but they provide a useful proxy. The crucial point of the chart is that the US has been in a cumulative process for the past 5 years but China hasn’t. Moreover, this divergence in the Wicksellian Differential in 2010 largely explains the relative stock market performance of the two countries since then.

Chart 2.0 US vs China stock market total return indices

Lessons learnt?

Investors therefore need to stop looking at GDP growth and start thinking about productivity growth as what matters for asset values is the rate of change of profit and not output. Although there are legitimate concerns about China’s rising level of local government debt, of more concern to investors ought to be how the rate of profit might start rising again. And analysing the detail of the current wave of infrastructure investment well provide the insight investors need to be bullish on China again.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks