The equilibrium rate of interest in the history of economics has been a surprisingly controversial topic. In a brilliant essay [from 1979] the Swedish economist Leijonhufvud stated that “the theory of the interest rate mechanism is the center of the confusion in modern macroeconomics. Not all issues in contention originate here. But the inconclusive quarrels – the ill-focused, frustrating ones that drag on because the contending parties cannot agree what the issue is – largely do stem from this source.” During the Great Moderation, the new neo-classical synthesis appeared to have put an end to this controversy. However, the current debate between different approaches to macroeconomic management between the Fed and the Bank for International Settlements, summarised here by Gavyn Davies , suggests the underlying controversy never really went away.

Central bank view

The new neo-classical synthesis argues that the equilibrium rate of interest is the rate of interest that maintains the economy operating at its potential. In a Taylor Rule framework the equilibrium rate of interest is generally considered to be the real rate of interest which implies inflation expectations are at 2%. If inflation expectations are constantly at the 2% level then fluctuations in actual output versus potential output are minimised, thereby maintaining the economy at its potential.

The concept of the real rate of interest is derived from the Fisher equation whereby economic agents estimate real rates of interest based on their view of inflation. Therefore a nominal long term bond yield plus the expected rate of inflation will produce the real rate of interest. This implies that actual real rates of interest cannot deviate too far from the expected rate of interest unless there is a catastrophic failure in the price mechanism. As a result the interest rate mechanism can be relied upon to coordinate the inter-temporal decisions of households and of firms. If inflation expectations are expected to rise then nominal rates will rise and conversely if inflation expectations fall then nominal rates will fall. Central banks attempt to influence long term bond yields by targeting short term rates using a variety of tools that impact inflation expectations, thereby leading to an adjustment of the long term nominal rate. The idea is to shift real interest rates back towards the equilibrium rate of interest which maintains the economy operating at its potential.

During the Great Moderation, central banks appear to have done a reasonably good job in influencing the bond market to maintain this so-called equilibrium rate of interest. If inflation expectations are set by the TIPS spread – the difference between nominal bond yields and inflation protected bond yield spread – and the result is a 2% level of inflation expectations, then the real interest rate can be said to be at its equilibrium rate. As chart 1 shows, the expected rate of inflation in red has fluctuated around the 2% mark since the series began in 1997. The yellow line shows the 5 year nominal rate and the blue line shows the 5 year TIPS rate. The green line shows the Federal Funds rate targeted by the central bank.

The ability of the Fed to influence long term rates once short term rates approach zero as they did in 2009 is however limited. Nominal rates fell and then rose based on inflation expectations. If the short term rate is static, then movement in the long term bond yield is related to the term premium or the difference between short and long term rates, which central banks have limited influence over.

The data in the charts suggests that real rates are where they should be at the moment given they are expecting 2% inflation. But it also highlights that there cannot be a single equilibrium rate of interest. The rate of unemployment today is far higher than pre-crisis levels but with similar levels of inflation expectations. As unemployment falls, the theory relies on nominal interest rates to rise to counter supposed inflationary pressures which then shock the economy into its new equilibrium level.

Chart 1: US Real interest rates and inflation expectations

So why is there still a controversy then? Opponents of the new neo-classical systhesis argue that current levels of nominal rates are too low, creating conditions for asset booms [and busts], with all the negative consequences they bring. Indeed such low rates are encouraging excesive leverage which can be observed in parts of the credit market and in real estate. Such levels of leverage are unlikely to be sustainable in the medium run. But if nominal rates rose, wouldn’t they choke off the nascent recovery the global economy is now mostly experiencing?

Fisher and Keynes vs Wicksell?

The theory of interest was expounded by Irving Fisher in his seminal book the Rate of Interest published in 1907. Influenced by the Austrian economist Bohm-Bawerk, Fisher agreed that the nature of interest was the income stream flowing from capital assets otherwise known as originary interest. Fisher then stated that the money rate of interest was set by the supply and demand for loans. With the two rates now appropriately defined, Fisher argued the money rates would naturally tend towards an equilibrium level equal to the rate of interest derived from capital assets.

In Fisher’s theory, if the return on capital is say 10% and the money rate is 5%, then loans will be made for projects until the marginal return on capital equals the rate determined by the supply and demand for loans. Fisher describes the farmer who will continue to improve his land to the extent that projects are only rejected at the point at which “the rate of return on sacrifice becomes less than the rate of interest.” In that respect, Fisher argued that there could not be a sustained significant difference between the return on capital and the cost of capital.

Fisher also seems to have influenced Keynes’ “own rate of interest” ideas in chapter 17 of the General Theory. According to Keynes, “As the stock of the assets which begin by having a marginal efficiency at least equal to the rate of interest is increased, their marginal efficiency tends to fall. Thus a point will come at which it no longer pays to produce them unless the rate of interest falls pari passu. When there is no asset of which the marginal efficiency reaches the rate of interest, the further production of capital assets will come to a standstill.”

The Swedish economist Knut Wicksell however took a different view. He argued that the returns on capital assets and the money rate of interest might diverge for a considerable period of time leading to a cumulative process of credit creation. In Fisher and Keynes’ world, such a divergence can only be a short term deviation given the natural tendency of projects to come on to the market using up the availability of loans until the two rates were in equilibrium again. As such the debate between the Fed and the BIS might perhaps be described as one between Fisher/Keynes and Wicksell. In order to determine whether Fisher/Keynes or Wicksell is closer to reality requires some form of empirical analysis.

It’s all in the data

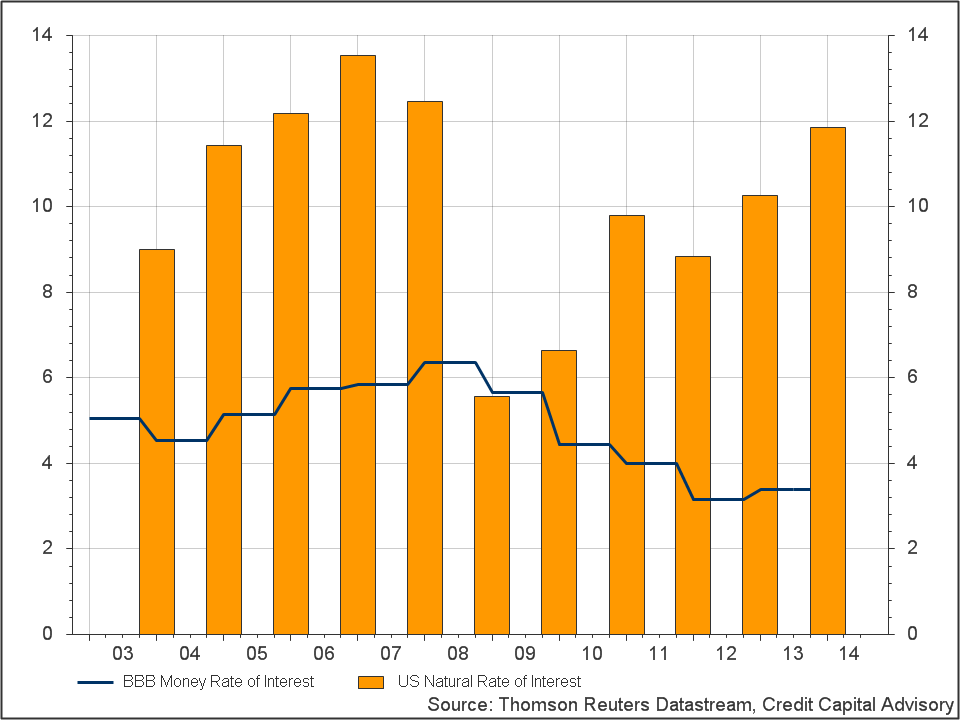

Empirical analysis of these two rates of interest in Profiting from Monetary Policy – the cost of loans for a 5 year maturity versus the return on capital – highlighted that in the last 30 years these rates have rarely been in equilibrium. In Profiting from Monetary Policy the 5 year government yield was used as a benchmark in order to provide a consistent long run time series for multiple jurisdictions. When the more appropriate BBB funding rate is used we find a similar story, albeit over a much shorter time frame as shown in chart 2.

Although the returns on capital have been derived from averages as opposed to marginal rates, which in imperfect markets are not accessible, the annualised changes provide directional indicators of the marginal rates. (Under conditions approximating perfect competition, marginal rates and the rate of return on capital converge). Thus if marginal rates were falling, one would expect to see a drop-off in average rates through time, and conversely rising marginal rates would correspond to rising average rates. Chart 2 demonstrates periods of rising marginal rates until 2006, followed by falling rates to 2008, with rates rising again from 2009.

Chart 2: US Natural rate of interest vs BBB cost of funding

The fact that these two rates are hardly ever in equilibrium with each other implies that there is no natural equilibrating tendency. Marginal rates of the efficiency of capital are not falling to the equivalent money rates as both Fisher and Keynes assumed would happen. The reason why this does not happen is that markets at the micro level are not perfect. Barriers to entry in many sectors are high, with some sectors only able to survive profitably with a handful of firms.

For example the credit rating business is dominated by three rating agencies, which are all extremely profitable with high “own rates” of interest. Although there have been a handful of new entrants into the sector in the last few years, this has had a limited impact on market share and existing returns. These newer agencies have mostly decided to specialise in certain asset classes and/or regions. However, it is the ability to provide a global service across asset classes that is central in being able to scale up and generate the kinds of returns enjoyed by the big three. The level of risk in breaking in to this market is substantial given the large upfront labour costs, the ever-increasing regulatory burden and a significant payback period.

In the large commercial aircraft market, Boeing and Airbus continue to dominate the space with high “own rates” of interest. However, the economics of aircraft design are such that if each firm sold fewer units, returns would be negative acting as a major disincentive for new entrants. Markets that display the characteristics expected by Fisher and Keynes would require minimal barriers to entry and lots of suppliers, which by definition are likely to be lower value added goods such as clothing. Advanced economies benefit from higher value added goods and services which by definition are difficult to replicate. The reality in most sectors in advanced economies is that conditions approaching perfect competition do not exist. Hence there is little reason to assume that these two rates should equilibrate at the macro level.

Besides new entrants being restricted from entering into the market place, incumbents generally do not undertake margin diluting projects. Fisher assumes that the farmer will continue to farm land up until the marginal return equals the cost of capital. The result of such a strategy is margin dilution and value destruction which is why this doesn’t tend to happen in the real world. For example Brazil’s soya farmers rather than continuing to buy up worse and worse land until the two rates equilibrate, have invested in R&D to maintain yields of both kinds.

Implications for monetary policy?

Given that these two rates are unlikely to be in equilibrium as projects are hardly ever undertaken at the margin, what can this framework tell us about monetary policy? The major benefit of such a framework is that it can clearly indicate when monetary policy is too tight leading to capital destruction as was the case in 2008 in the US. But it can also identify a cumulative process of credit creation which happened between 2002 and 2007 and now from 2009 onwards.

The framework also highlghts why an extended period of quantitative easing has an increasingly limited positive impact on the economy, only serving to stoke the cumulative process of credit creation. The logic of the argument that a fall in the value of money through an increase in the supply of money increases aggregated demand (AD) assumes that this would make some projects profitable, thus stimulating investment. However, as we have seen projects are generally not undertaken at the margin implying that monetary stimulus is unlikely to have much of an impact on AD. The prevention of capital destruction permitting agents to refinance will clearly have a stabilising effect on AD. Furthermore, an extended period of monetary policy might also permit agents to deleverage to such a point that they start spending again but this assumes that agents’ expectations are such that they want to start spending. A fall in the value of money might dampen expectations to such an extent that there would be even less motive to increase the rate of investment until money rates were back to levels expected in a “normal” economy. This was Keynes’ great insight in the General Theory related to his liquidity preference. Indeed, there has been very little analysis by central bankers of the negative impact on expectations caused by loose monetary policy, which by definition indicates that things are bad.

Rates too high or too low?

It makes little sense to try and generalise about the level of rates across countries given the relationship between the returns on capital and cost of capital is country specific. The data in table 1 shows the extreme variation in the levels of returns on capital.

Table 1: Comparison of Natural Rates of Interest (Weighted own rates of interest)

Country 2013

France 3.8%

Germany 9.3%

Japan 6.8%

USA 11.9%

The data highlights three key findings.

1) The returns on capital in the US are now back at levels associated with “normal conditions”, hence the value of maintaining loose monetary policy is significantly reduced. Although wage growth remains stagnant, this is more related to the challenges of globalisation and the substitution of capital for labour than any ongoing structural issue with the US economy.

2) It is abundantly clear that monetary policy remains too tight for France but not for Germany whose rates are approaching “normal conditions”. When the returns on capital fall due to a slump in aggregate demand, ensuring that the cost of capital is below the return on capital is an absolute necessity to prevent capital destruction which is now happening. The ECB clearly needs to be doing far more as numerous commentators have been arguing, although natural rates in Germany imply monetary policy will be too loose for Germany. This of course gets to the heart of the problem within the currency union itself.

3) As for Japan, its rates are back to the 6% level where they have traditionally been. As such there is very little validity to the argument that maintaining loose monetary policy will be able to increase the level of profits, income and spending beyond this. The reason why the returns in Japan have traditionally been about half those in the US is related to supply side economics and productivity growth. It is this more than anything else that Japan desperately needs to focus on.

The data for the US implies that interest rates should start to rise in order to prevent the cumulative process of credit creation from increasing the level of systemic risk. High yield debt is looking extremely frothy at the moment and when interest rates eventually do rise, risk premiums will jump as will defaults. The longer the cost of capital remains substantially below the returns on capital, the greater the volume of money will be invested in highly leveraged and what will become risky investments. The Fed is likely to remain focussed on inflation, particularly wage growth, as an indicator of the equilibrium rate of interest. Given the downward pressure on nominal wage growth due to globalisation and the substitution of capital for labour, interest rates are likely to stay where they are increasing the rate of the cumulative process and credit creation.

However there is a strong case that a marignal rise in real interest rates in the United States may actually lead to higher AD. Marginally higher interest rates are likely to spur faster productivty growth with firms having to find other sources of profits instead of refinancing at lower rates and benefitting from depressed exchange rates to enhance export competitiveness. If this productivity growth were then to be passed on to workers in the form of falling prices this will lead to rising real wages and higher AD. Finally, the Fed by signalling that the Crisis is now over and that things are moving back to normal may well have a strong positive effect as firms ramp up their investment programmes with improved expectations.

Unfortunately while central bankers continue to believe that the global economy functions according to a model of equilibrating tendencies, with inflation being the signal of divergence from equilibrium, this is unlikely to happen. As Leijonhufvud perceptively argued 35 years ago, understanding that the interest rate mechanism remains the source of most contention in economics and finance still needs to be recognised. Failure to do so will catch investors and policy makers short changed once the market realises that highly leveraged entities are unable to pay back what they have borrowed leading to capital destruction and the next economic downturn.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks